Attacks on the Nord Stream gas pipelines have highlighted the rising threats to Europe’s energy infrastructure and submarine cable networks.

In a nutshell

- Risks to subsea infrastructure have been overlooked

- Russia maintains diverse capabilities for sabotage

- Western allies are mounting joint defenses

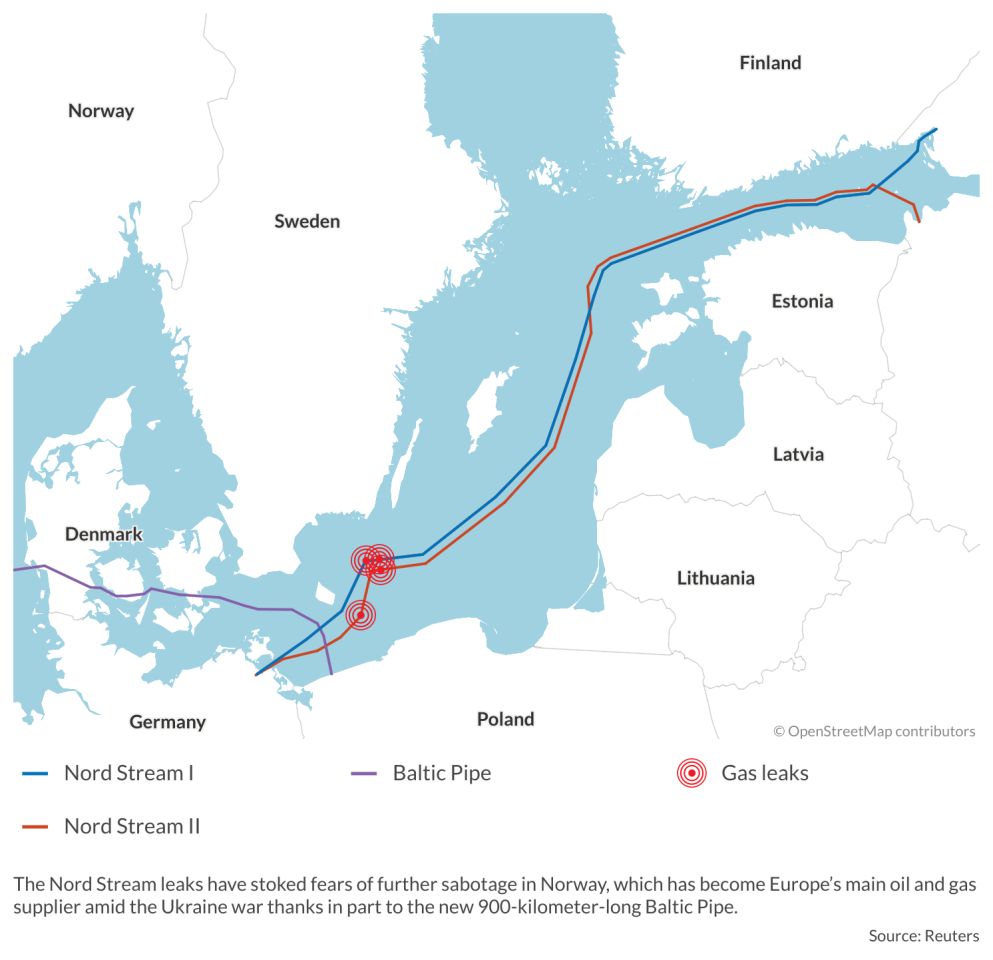

On September 26, 2022, Sweden and Denmark discovered four major leaks in Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2, the 1,224 km subsea gas pipelines connecting Russia to Germany and Europe. Two of the leaks occurred in Sweden’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and two in the Danish EEZ, and in both countries, seismometers had recorded explosions of up to 2.3 on the Richter scale in their immediate vicinity. American intelligence services had already warned allies last summer of the possibility of destructive attacks on pipelines and other critical infrastructure (CI) assets.

Immediately, the governments of Sweden and Denmark declared the leaks a result of deliberate sabotage, with the four blasts seemingly planned and implemented in a coordinated manner. The incidents prevented the future flow of gas through either pipeline from Russia to Germany. However, Nord Stream 1 was already suspended by Russian President Vladimir Putin himself at the end of August; Nord Stream 2, politically controversial for years, had never been in operation, and its certification by Germany was suspended just before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

In addition, the Nord Stream attacks also caused the world’s largest-ever recorded leak of methane gas, which is up to 80 times more consequential for climate change than carbon dioxide.

A few days later, Germany experienced more sabotage, when fiber optic communication cables serving the German rail network were similarly cut at two different points in a “malicious and targeted” action. This led to prolonged train disruptions, even affecting international connections. In both cases, the sabotage was planned with detailed intelligence – indicating the involvement of a state actor.

Recent physical attacks have highlighted the increasing hybrid threats posed to European critical infrastructure.

A week before the pipeline sabotage, Norway had observed unidentified drones above six offshore energy infrastructures belonging to Norwegian oil and gas producer Equinor, and three other facilities. The drones were thought to be launched by Russian ships.

Since the Nord Stream explosions, Norway – which has become Europe’s main oil and gas supplier amid the Ukraine war – has feared further sabotage of its own energy infrastructure by Russian intelligence services and special military forces. The country has more than 9,000 km of pipelines in addition to internet cables and electricity cables running to European Union countries. The new 900-kilometer-long Baltic gas pipeline, with an annual capacity of 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) from Norway via Denmark to Poland, was just inaugurated last September.

These physical attacks have highlighted the increasing hybrid threats posed to European CIs and the need to make them more resilient. Both the European Parliament and European Council had already agreed before the Nord Stream attacks to deepen the legal framework for protecting European CIs, as well as strengthening a key 2008 Council directive, but the law will only come into force next year.

What is critical infrastructure?

Although the topic of critical infrastructure protection is not new per se, it has mostly been the province of technical experts over the past two decades – lacking any major European debate on new vulnerabilities, risks and effective countermeasures to make CIs more resilient.

For both security experts and the European Commission, CIs are considered particularly vulnerable due to their importance to the survival of the state and the maintenance of its vital functions. These include information and telecommunications systems, as well as transport, energy supply, healthcare, finance, and other sensitive public and private services. These CIs are characterized by a high degree of internal complexity and interdependence as well as vulnerability, as highlighted by the 2021 floods in Germany’s Ahr Valley.

At the same time, the specific responsibilities and regulations among EU member states are varied, and until recently lacked common security standards or an obligation to report serious sabotages or cyberattacks. In countries like Germany, this is also the case between the federal government and the state level, as well as between different federal ministries.

Further, over 80 percent of all CIs in Europe are controlled and operated by private companies. This requires continuous cooperation between public authorities and the private sector. But until a few years ago, this was not present in most EU countries, nor were the respective responsibilities between the state and the private sector clearly regulated or mutually agreed.

Facts & figures

Although the European Commission raised awareness over critical infrastructure protection more than a decade ago, most of its recent studies on future CIs and new security challenges focused on cybersecurity. CIs, and critical energy infrastructure in particular, depend on a stable power supply and secure access to the internet.

Although physical attacks on CIs have still taken place worldwide over the past 15 years, guarding against them lost some urgency in Europe after the threat of Islamist terrorist activity subsided. In addition, the growing need to protect an ever-increasing amount of critical underwater infrastructure (such as pipelines, internet cables and power cables) has been largely overlooked by both governments and industry, in part because safeguarding them is usually even more costly and demanding than CIs on land.

New frontier

Dependence on a limited but increasing number of fiber optic cables that make up the global internet network has become a growing security problem in the face of new geopolitical conflicts.

As much as 99 percent of global digital communications flow through a network of submarine cables on which the world’s economy and digital services fully depend. Currently, 95 percent of international internet traffic is secured via around 200 large submarine cables – each of which can transmit about 200 terabytes per second – and some 340 further main cables. The longest cable is over 40,000 km and has dozens of landing points from Germany to Singapore and Australia, across several oceans and connecting several continents.

These 1.3 million km of cables guarantee an estimated $10 trillion worth of financial transactions every day. They are also linked to each other in just 10, inherently vulnerable local positions. According to some forecasts, the transatlantic data volume will double every other year.

While naming the culprits behind gas pipeline sabotage might already be difficult, attributing responsibility for damaged internet cables could be even harder, as they can also be damaged inadvertently by earthquakes, ships and submarines. And the vulnerability of Western high-tech industries to CI exposure results not only from the possibility of sabotage, but also from espionage via the tapping of submarine cables.

The overall strategic importance of subsea CIs also includes an increasing number of subsea power cables, which are needed in parallel with expanding offshore wind and maritime solar parks to connect them to onshore power grids. The future security of the electricity supply in Europe and elsewhere will increasingly depend on underwater power cables. Underwater CIs thus have new strategic importance for the EU, amid the backdrop of Russia’s hybrid warfare against Ukrainian CIs and its alleged sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines and German communication cables.

Facts & figures

Selected attacks on critical energy infrastructure

- 2022: Large-scale Russian cyberattacks on European CIs, such as wind farms, and energy companies

- 2021: Ransom cyberattack by a known Russian hacker group (with links to Russian intelligence) against the American Colonial Pipeline, disrupting supply for households, industry and the military for days. Against Washington’s recommendation, the oil pipeline operator pays a ransom to end the attack.

- 2019: Houthi rebels in Yemen employ drones and cruise missiles against Saudi oil and gas infrastructure

- 2017: Russian cyberattack on Ukrainian IT infrastructure, including energy assets

- 2015: The first state-backed cyberattack on critical energy infrastructure and the power system of another country (Ukraine)

- 2013: Physical attacks by terrorist militias strike a European gas production site in Algeria

Scenarios

Escalating Russian attacks

According to unofficial NATO sources, Russia has many years of experience with military exercises aiming to cut through submarine internet cables, even in the Atlantic Ocean, with targets at a depth of more than 6,000 meters. Norway has also accused Russia of cutting underwater acoustic sensor cables off its northern coast at the beginning of 2022. As usual, the Kremlin has denied any responsibility in that incident, as it did regarding the Nord Stream pipelines.

However, Russia’s Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research (known as “GUGI”) maintains many espionage and quasi-military ships and special submarines. This includes the “Belgorod,” the largest submarine in the world, and the “Yantar” research ship. These and other vessels can be used for unusual deep-sea operations, using mini-submarines, underwater drones, unmanned underwater vehicles and special diving forces to cut underwater cables.

The geopolitical competition between the United States and China has heightened the relevance of underwater internet cables, especially regarding the development of Huawei’s 5G network over the next decade.

Western counterstrategies

Already in February 2022, France adopted a new strategy “seabed warfare.” As a result of pipeline sabotage and alleged drone activity over its offshore oil and gas production sites, Norway and its NATO allies have stepped up surveillance and maritime patrols to protect energy CIs by air, sea and even by tracking Russian submarines in its EEZ. Last November, Norway and Germany proposed a NATO-led hub to protect underwater CIs. And in January of this year, NATO and the EU agreed to collaborate more closely in security and defense policies, including the creation of a joint task force on resilience and CI.

A June 2022 European Parliament analysis of security threats to submarine cables noted that while the risk of a major breakdown of the global internet submarine network appears low, as it could equal an act of war, “symbolic attacks on cable connections are to be expected. Attacks and sabotage by extremists and criminal groups are equally probable.”

A newly proposed Council Recommendation by the European Commission calls on member states to carry out new risk assessments and accelerate work to strengthen the resilience of EU CI. Strengthening critical infrastructure protection encompasses three priority areas: readiness, response and international cooperation, with a priority on readiness. The document proposed a greater role for the Commission in addressing threats and improving cooperation between EU member states and third countries, in particular around transnational CIs. This includes carrying out joint and coordinated risk assessments under the revised Network and Information Security Directive, which is based on a political agreement reached on these challenges last May.

The directive also required member states to implement both the revised version and the Directive for Critical Entities’ Resilience. The latter aims to strengthen the ability of states to protect their CIs from a range of security risks and to improve responses to terrorist attacks or natural disasters. But regarding submarine protection of critical infrastructure, an intra-EU dialogue on best practices at a state level is central – as cable protection invokes overlapping areas of maritime security, cybersecurity, ocean governance and infrastructure policies. It may also lead to closer cooperation between the EU and NATO, as well as between the EU and the United Kingdom, as it is in the interests of all these parties and cannot be solved by a single government or organization.

To respond adequately to heightened hybrid warfare against Europe and transatlantic underwater internet cables, the EU will not only be forced to adopt new regulations, directives and networked-security concepts. To make underwater CIs more resilient, the EU will be pressed to build up a strategic reserve of sufficient internet, communication and power cables, as well as ships for their quick repair. At a time of increasing geopolitical conflict, enhancing resilience will become an essential part of both protecting critical infrastructure and of Western deterrence against efforts at CI sabotage by major powers and other aggressors.